Ginger and I just returned from an amazing trip to Kyoto, Japan. We were able to meet up with my former professor, mentor and friend Glen Kaufman who has maintained a presence in the city for 30 years. His knowledge proved invaluable for selecting our destinations and maneuvering through the city. Our daily pilgrimages consisted of a dozen Buddhist and Shinto temples and shrines, art museums, galleries and the streets and neighborhoods of the 1200 year old community.

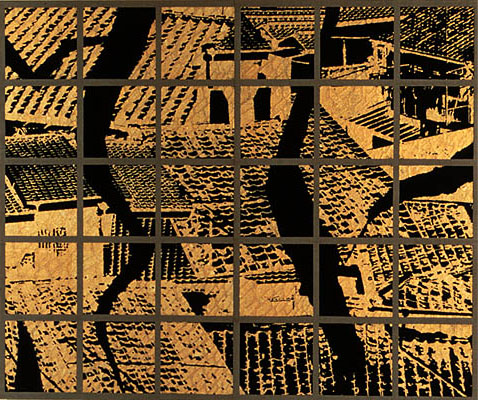

Kyoto is a direct influence on Glen's artwork, especially his "Broken Cities" series from the mid-90s.

Glen Kaufman Broken City, Kyoto/Jofukuji, silver leaf on silk, screenprint, 26" x 30"

Glen Kaufman Broken City, Kyoto/Jofukuji, silver leaf on silk, screenprint, 26" x 30"While studying his oeuvre in college, the graphic inspiration for Glen's work seemed obvious.

- Metal leaf is a regularly found element in ancient Japanese screen paintings, like the work of the Kano school.

- The sea of rooftop clay tiles of Kyoto can be seen through his studio window.

- The background silk is reminiscent of kimono fabrics.

- The overlay grid reflects the pattern of shoji screens.

- Japan is an earthquake prone area, and the "cracks" or broken iconography in the work symbolize not only the physical science of the area; but also symbolize the cultural shifts that move Kyoto away from its history and into the future.

Kano Eino Birds and flowers

of the four seasons (17th century)

Kano Eino Birds and flowers

of the four seasons (17th century)Yes, the use of metal leaf can be seen in the screen paintings of Nijo castle; but gold and silver leaf are also found throughout Kyoto ornamenting sculptural and architectural elements and artifacts. Its shimmering detail can be found throughout the city, not just in temples and shrines. Then, of course, there's the Golden Pavilion.

Image by jeffkole via Flickr

The presence of kimono, however, is not as obvious. But when you do see these flowing wrapped gowns, they make an incredible impact. While most Japanese opt for more modern attire, there are a significant number who do wear traditional kimono when shopping, visiting temples or performing cultural activities. When you see one of these individuals, the power of the kimono is apparent against a sea of cell phones and designer sunglasses. The beauty in the material, patterning and craftsmanship is unparalleled, especially when presented alongside the detached sleekness (and sometimes gaudiness) of the contemporary urban environment.

Katsura Imperial Villa Teahouse, Kyoto

When staying in traditional Japanese homes or inns (ryokans), you are regularly presented with the shoji grid. It's an ever-present reminder that you're not in Kansas (or Savannah) any more. The grids and paper panels only barely disguise the images and sounds from the other side. With direct-enough light, you can see right through them. The rigidity of the grid can be found not just in the screens; but also in the assembly of wall panels and the careful placement of tatami mats. We give the Swiss a lot of credit for the grid in graphic design; but that may be more correctly placed on the traditional Japanese aesthetic.

The "cracks" in the work are pure artistic license and symbolism. They are a visual representation of an abstract concept. Only the artist can definitively speak to their meaning. From our own understanding, we can infer social, scientific and political explanations for their presence. But ultimately, that is for each individual to discover. That's what great contemporary art is all about: The assembly of known components into a cohesive whole that is open to interpretation.

While I'm grateful for this trip because of time spent with friends and the experiences that only come from world travel, I'm most appreciative of the new-found understanding I have for art and design that I already loved. The trip was a source of constant inspiration and understanding that will never be forgotten.

Ginger, Lee and Glen at the Imperial Palace, Kyoto